|

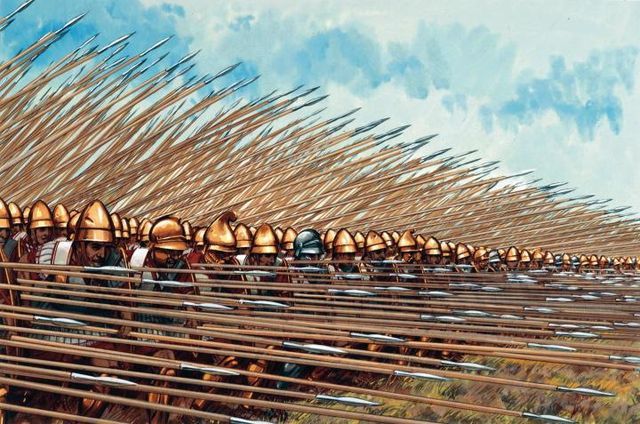

| Book Cover Art |

Dear Reader,

Today, we are going to review Hellenisitic Infantry Reform in the 160s BC, by Nicholas Sekunda, a professor at the University of Gdansk. Published in 2001, this book makes an argument that around 160 B.C.E., the Ptolemaic and Seleucid Kingdom's reformed their armies along the lines of the Roman Republic. Previously, according to Sekunda, the mainstay of the heavy infantry in these armies had been sarissa phalanxes, but around 160, they began adopt Roman manipular tactics.

The first portion of Sekunda's work deals with Ptolemaic Egypt, and this should not be surprising, as nearly every part of the Ptolemaic state is better historically attested than its Seleucid counterpart. Sekunda's evidence is formidable: he draws on several Stele from Hermopolis, These Stele record unit officers and organization for the Hermopolis garrison. From the organization on the Stele, it appears that these troops where the organized along the lines of a Roman maniple, rather than a sarrisa phalanx. Also draws on a number of archaeological sources, including tombstones, like that of Salmas of Adada (on the book cover, above) and Dioskourides of Balboura (below).

Sekunda also uses the Kasr el Harit shield in order to make his case that Ptolemaic infantry had adopted Roman tactics on a large scale. This shield found in Egypt, matches Polybius' description of a Roman Scutum. (Poly. 6.23. 2-5) Based on the artifacts found in proximity to it, the shield dates in the late 2nd Century B.C.E., around the time of Sekunda's claimed reform. Peter Connolly's drawing of the shield is below.

| Peter Connolly's rendition of the Kasr el Harit shield |

On the whole, Sekunda convinces the reader that on some level, after 160 B.C.E., the Ptolemaic army did perhaps adopt units in the Roman style. However, he runs into trouble when he attempts to claim more broadly about the Seleucid army in the same period. Using Polybius' descriptions of the army of Seleucid King Antiochus IV from the parade at Daphne, Sekunda argues that the 5,000 men "armed in the Roman fashion" were a test unit subsequently adopted by the entirety of the Seluecid army.

His evidence for this comes from the fact that at the Battle of Beth-Zachariah, in 162 B.C.E. the Seleucid army appears to have been operating in a flexible manner, which would better fit a Roman maniple than a sarrisa phalanx. However, here, Hellenistic Infantry Reform runs aground. The author of I Maccabees, who describes the Battle of Beth Zachariah, refers to the disposition of the Seleucid War-Elephants, saying, "they distributed the beasts among the phalanxes, with every Elephant being assigned a thousand men." (καὶ διεῖλον τὰ θηρία εἰς τὰς φάλαγγας καὶ παρέστησαν

ἑκάστῳ ἐλέφαντι χιλίους ἄνδρας τεθωρακισμένους ἐν ἁλυσιδωτοῖς) (I Macc. 6.35)

Sekunda argues that the description of the soldiers

in the phalanx is more in keeping with a Roman legionary, each of these

thousand men assigned to the Elephants, "had coats of mail, and helmets of

brass." Sekunda commits a number of possible errors here: first of all, he

assumes that the phalanxes and the thousand men assigned to each elephant are one

and the same, which is not grammatically clear. Is it not possible that these

soldiers could be a portion of the "Romanized Infantry," mentioned at

the parade of Daphne? Or, equally likely, that these men were Thorakites, a

type of armed infantrymen who used a shield and thorax who were previously

included in Seleucid armies?

If the author of Maccabees explicitly states that

the elephants were distributed among the phalanxes (φάλαγγας) should we not

take him at his word? Sekunda argues that in this case, "phalanxes"

simply means infantrymen, but later, when describing Plutarch's account of a

Armenian army, he insists that the statement, (τῶν μὲν εἰς σπείρας, τῶν δ᾽ εἰς

φάλαγγας συντεταγμένων,) means that the Armenian army was a literal mix of

cohorts and phalanxes. It seems to me that it would be more historically

responsible to assume that there was an actual phalanx present at Beth

Zachariah.

Though failing to convince fully when describing

Seleucid military reform, Sekunda has amply succeeded showing that the late

Hellenistic armies were more complex and adaptable than has previously been

thought. He is at his best when using solid literary and archaeological

evidence, particularly when describing the Ptolemaic and very late Hellenistic

armies used by Pontus and Armenia. If you are interested in the armies of the

Hellenistic world or the military systems that Caesar and Pompey faced, this

book is for you!

Thanks for reading,

Alex Burns