|

| At Spartan Hoplite at rest, Peter Connolly |

Dear Reader,

As historians and scientists often note, I am only able to compose this work because, in a figurative sense, I stand on the soldiers of intellectual giants. Our understanding of conflict in the ancient world advanced by leaps and bounds in the twentieth century, as a result of the life's work of dedicated ancient world specialists. The work of individuals like Peter Connolly, Donald Kagan, Adrian Goldsworthy, Victor Davis Hanson, Robert Strassler and other individuals less well known, like Paul Bernard, Bezalel Bar-Kochva, Nick Secunda, Angelos Chaniotis, and Paul Bardunias come together to make our knowledge of the Classical Greek and Hellenistic warfare possible. I am grateful to be able to contribute to this in a tiny way.

In this post, I want to briefly outline two types of infantry soldier we will encounter in the Greek world, how they are different, and what makes them distinct. Before continuing- realize, much like today, there were many different types of soldiers present in the Greek - this is not a comprehensive list, nor should these types of soldiers necessarily be viewed as the main or most important type of ancient Greek soldier. However, they are perhaps the most distinct and recognizable.

1. όπλίτης (heavily armed soldier, or Hoplite)

This type of soldier emerged in the sometime in the 700s or 600s B.C.E. As pictured above, the Hoplite armed himself with a six foot long spear (δόρυ, or "dory") and a large, domed circular shield about 3 feet in diameter, an ασπίς (aspis). It is interesting to note that in a military context, the aspis referred to the left, while the dory referred to the right. These men fought together in a military formation called a Phalanx, which, to prevent it from being confused with a second type of phalanx discussed below, we will call a Hoplite phalanx. Historians continue to debate the exact nature of combat between two of these opposing forces, something we will be coming on to in a future post.

So, in the early period of Greek history, from around 700-350 B.C.E. this type of soldier fought, apparently in formations between 8 (the norm) and 25 (the exception) men deep. Despite images like the one above, and portrayals in film, there was little "uniform" about these warriors. Some fought in metal and leather armor, others wore linen tunics, some appear to have even fought nude. Perhaps the most famous Greek army, the Spartans, standardized their forces in two ways: by the year 400 B.C.E., Spartan forces wore red cloaks, and had a stylized capital Greek letter Lambda (Λ, for the Spartan homeland, Λακεδαίμων, Lakedaemon.) To be a good Hoplite meant standing in the formation with your fellow citizens, and defeating the enemy through combined effort. This is evident, as after the Battle of Platea, the Spartans ignored a soldier who had committed an act of exceptional valor, and honored a man who had stood at his place in the Hoplite phalanx.

The fact that this type of soldier endured for over 350 year, does not mean that they remained fixed and static in development. Figures such as Epaminondas of Thebes and Iphicrates of Athens attempted to reform how Hoplites were employed, and influenced future tactical thinkers.

|

| A Phalangite/Pezhetairoi |

Around the 350s B.C.E., a massive power shift came to Aegean world, as a regional kingdom in Northern Greece, Macedon, became the overlord of Greece. It is likely that Macedon's ambitious king, Phillip II, utilized a new type of soldier in order to conquer the Greek mainland.

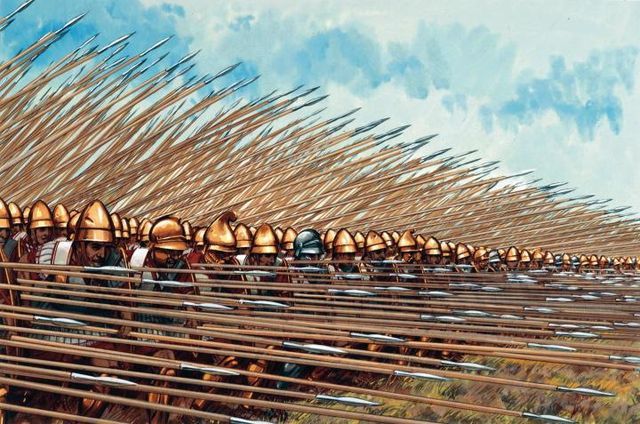

Ancient sources are somewhat mixed on what to call this new type of soldier. Arrian, the most famous biographer of Alexander "the Great" refers to these men as Pezhetairoi, or "Foot Companions." By contrast, our two other good sources for information on the Hellenistic era, Diodorus Sicilus and Polybius of Megalopolis refer to these men as "Phalangites." That is the term which we will employ in our discussion of these soldiers. These Phalangites used a pike, the σαρίσα, (Sarissa), which was possibly up to 18 feet long, much longer than the dory. While historians disagree on exactly when the Sarissa came into use, it may have been used as early as the Battle of Choronea in 338 B.C.E. The Phalangites formed the Sarrisa Phalanx (an unwieldy term but better than "Phalangite Phalanx"). Macedonian generals arrayed the Sarissa Phalanx at varying depths, with 8, 16, and 32 being some of the most common. Since the Phalangites often used a smaller shield than the Hoplite, they depended on the deep hedge of spears (perhaps 3, 4 or even 5 projecting beyond the front rank of men) in order to defend themselves from enemy attack.

|

| An advancing Sarissa Phalanx |

Once again- these were not the only types of infantry in the Greek world. We will get on to the θυρεοφοροί, θώρακταί, ψίλοί, and others in time. If none of this is new information to you- don't despair. We will get into more technical debates further up in the blog. I want to begin simply by outlining a base set of knowledge, from which we can proceed to more specific ideas.

Thanks for reading,

Alex Burns

No comments:

Post a Comment